It seems to me, however, that one of the most important issues for people is that they don’t want the government getting in the way of them living their life. They don’t want the government prying into their personal life, or taking their hard-earned money, or hampering putting bureaucratic red tape in the way of them going about their business. The majority of complaints about government seem to be about taxes and regulation. When it comes to spending, most people tend to be opposed to it in the abstract, but in favor of specific spending measures when they are presented to them. Most of the general opposition to spending tends to be based on fears about inflation, debt, and taxes.

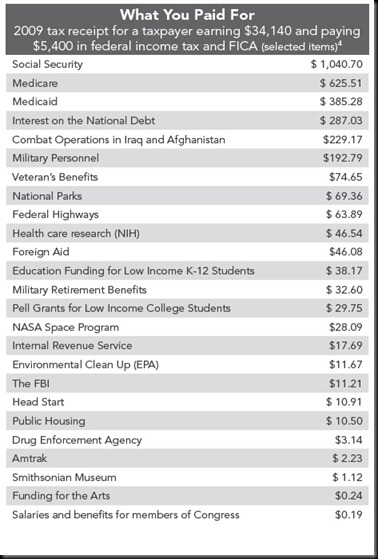

This picture has been circulating the blogosphere lately:

It shows, in concrete terms, what expenses our tax dollars go towards. The first two items are considered “third rails” in politics – to touch them is political suicide. The third item enjoys a great deal of support as well. The fourth item is considered necessary, though as I’ve pointed out before, it really isn’t. Items commonly attacked by would-be deficit hawks, such as national parks or public housing, are relatively minor expenditures.

The deficit, however, really needn’t be a problem. As I’ve pointed out before, we can have a debt-free monetary system that frees us from the need to borrow altogether. This would get rid of the fourth item on that list right away, allowing for a dramatic reduction in the tax burden.

So what about taxes? One gripe people often have about spending is that it the government has to take the money from someone in order to give it to someone else. This sentiment particularly underlies hostility towards social spending for the underprivileged. “Redistribution of wealth” is associated in many people’s minds with socialism, and images of bread lines in the Soviet Union are evoked to scare people from the consequences of such policies. It is claimed that anti-poverty policies actually make the problem worse, because the taxes to pay for them are taken from those who create jobs.

The historical record does not appear to support this position, largely because it oversimplifies a much more complex phenomenon. It neglects the fact that low-income recipients of tend to spend most of their incomes, rather than save. It also neglects the amount of capital that comes from bank loans, which are driven by overall economic performance. This means that they create demand for the products that businesses create, thus helping business. Nonetheless, the logic behind the idea of taxes hurting business is sound, all other things being equal.

However, not all taxes are equal. John Stuart Mill pointed out that there is a difference between productive and unproductive labor, and pointed out that higher incomes are more likely to pay for the latter than the former. Thus, he said, progressive income taxes are not likely to interfere with production so long as they fall mainly on unproductive labor.

There is, however, another tax which takes only unearned income, which is not obtained by labor of any kind, whether productive or unproductive. That tax is a land value tax. I won’t go into too much detail about this fiscal policy, as much of the rest of this blog is devoted to it. I will simply point out how it undermines the arguments usually put forward against taxes.

An important aspect is its non-distortionary character. Unlike other taxes, it does not raise the price of the commodity that it taxes – in fact, it lowers the price. Not only does it tax only the unearned wealth derived from the community, but it also encourages production and wealth-creation by penalizing idle speculation. It also perfectly matches public expenditures on infrastructure, such that whatever government spends on the public, it gets back in taxes, without having to raise or lower the tax rate.

A land value tax could also be collected without the government prying into people’s private lives. There will be no need to account for people’s sources of income. All that will need to be done is periodic land value assessments, which can be performed without the slightest intrusion of privacy. People might be very protective of their jobs, investments, and other sources of income, but it hardly makes any difference who knows how much a piece of land costs. That information is attached to the land itself, which is in plain view for all to see, rather than to the individual owning it. This also makes it very difficult for people to evade the tax, and requires less overhead to collect.

Additionally, land value taxation would streamline government spending. As I’ve pointed out previously, the increase in productivity from soaking up unearned income would increase wages, eliminate involuntary unemployment, and ultimately help end poverty as we know it. This is accomplished by the tax itself, regardless of how it is spent. This means that most of the social programs which conservatives and libertarians like to complain about would essentially become obsolete. Social security could furthermore be replaced by a citizen’s dividend, taken from a small percentage of the annual revenue.

Debt-free money would also decrease the cost of infrastructure by eliminating the interest on the debt. Demurrage would further lower that cost by giving money itself a negative interest. This would in turn lead to zero interest on loans, which would eliminate the “impossible contract” problem of ever-expanding interest. Without this problem of interest, we overcome the need for constant growth, which can help keep government and the private sector alike at a sustainable scale.

Furthermore, federalism can be restored by dividing the monetary power and the tax base between the federal and state levels. To the federal government belongs the money power. They should have the power to issue debt-free, negative-interest money for the funding of infrastructure. Much of this money can be allotted to the state governments to leave the infrastructure spending to their discretion. The states can then levy taxes on the land value which is bolstered by this infrastructure. The federal government can then tax a portion of this revenue from each state according to its total land value. This arrangement keeps taxes primarily at a local level, while the federal government provides the liquidity to support the states in these endeavors.

The relatively small percentage of tax revenue going directly to the federal government can go towards national expenditures such as a national healthcare system, where Medicare is made available to all. This may sound like “big government” to some, but we should understand that countries with national healthcare systems spend less, both publicly and privately, on their healthcare. Also, such a system would not preclude private insurance companies from providing additional or alternative insurance.

Another major cut that could of course be made would be in the military. America currently accounts for 54% of all the world’s military spending. That means that all the other countries combined still wouldn’t match our military expenditures. I don’t think I’m alone in finding that a bit excessive. Of course, even if we suppose that the world is dangerous enough to warrant this level of expenditure, there are other things we can do to reduce this danger and encourage peace.

One of them is to end our dependence on foreign oil. Easier said than done, obviously, but there are signs of hope. The military itself could be a leader in this effort, as victory on the battlefield necessitates that they make optimal use of resources. We can also create a smart, integrated power grid that efficiently distributes electricity where it is needed most. A feebate could be levied on automotive sales to encourage the most fuel-efficient vehicles in each size class that current technology allows. Taxing resource rents would further create disincentives for the waste of natural resources while incentivizing recycling and efficient use.

Eradicating global poverty would also eliminate much of the need for military intervention. Poverty eradication may sound like a big government project of its own, but when we understand the dynamics of globalization, it becomes clear that much of what needs to be done is simply to get out of the way. The IMF, World Bank, WTO, and several other international institutions have used debt to push poor countries into neoliberal policies which have been disastrous for their populations while benefiting Wall Street investors. There are, of course, reforms that such countries could and should make to their own economies, and we can lead them in doing so. But such leadership should come by example, not coercion.

So, to review, what cuts can we make to have a government that is small and efficient as well as responsive? By shifting the tax burden to land values and other rental income, we get rid of most government meddling in the private sector. Such tax policies also get rid of the poverty, reducing the need for social spending. A debt-free, negative interest monetary system would then get rid of the national debt and the interest we have to pay on it. The roles of taxation and money creation can be divided up in such a way as to restore federalism to the country. A smart environmental policy which gets incentives right and taxes resource rents would reduce our independence on oil and in the process reduce the need for military expenditures, as well as reducing the need for cleanup expenditures. The result is a government that is far more efficient and can do more with less. Government can be smaller and less intrusive while also being responsive to human needs.